No matter how many Clorox wipes they buy, or how far apart they place desks, schools will not be returning to normal anytime soon, due to continued public health concerns surrounding COVID-19 transmission. The grief of disrupted routines, short-circuited friendships, and delayed academic milestones that had sunk in by spring has been replaced with the stress of ongoing uncertainty.

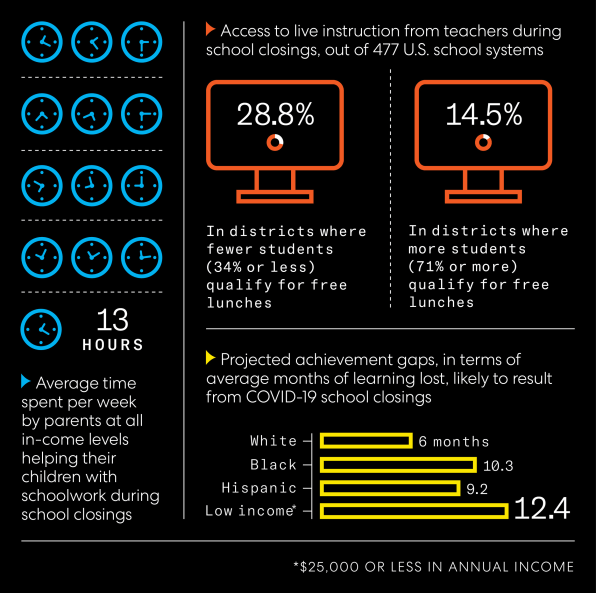

Among educators, a different kind of grief has been taking hold, as they’ve realized that school closures have created a variance in students’ progress that is so great, it renders grade levels almost meaningless. While some schools achieved a degree of success with video-based lessons and digital assignments submitted via tools such as Seesaw and Google Classroom, many struggled to adapt—and many students have fallen behind. In May, the nonprofit Northwest Evaluation Association (NWEA) and collaborators at Brown University and the University of Virginia projected that students would return to school this fall having made only two-thirds of their typical school-year gains in reading and less than half of their typical school-year gains in math. McKinsey & Company estimates that at least 232,000 additional students will drop out of high school before the end of this school year—an increase of nearly 20% from the previous year.

“The remediation needs [over the] next year are going to be extraordinary,” says Robin Lake, director of the Center on Reinventing Public Education. “It’s unfathomable to me how a sixth-grade teacher will cope with the sixth-grade pacing guide she’s got in front of her. I don’t see any option but to innovate.”

Much of the creative thinking in schools in recent years has centered around personalized learning, a term for the practice of modifying lessons, pacing, and subject matter to meet the needs and interests of individual students. In theory, personalized learning seems an ideal way to tackle the problem at hand. But many educators are wary of personalized learning as a mind-numbingly rote embrace of technology. For example, there are an increasing number of ed-tech products, marketed as personalized, that use adaptive algorithms to serve up a sequence of multiple-choice questions—preparing students for standardized tests but not much else. Two years ago, students at one Brooklyn school walked out in protest against a personalized-learning platform called Summit Learning; in a letter to Summit financial backer (and Facebook CEO) Mark Zuckerberg, they called the platform “boring” and said that it had eliminated “human interaction, teacher support, and discussion.”

And yet educators at schools where personalized learning is viewed as an overarching philosophy, rather than a digital panacea, say that adapting to the pandemic has been relatively painless, and that students are continuing to progress in their studies. The key difference between their approach and the popular narrative around personalized learning is that these educators have built their schools around the idea of student agency. In other words, their students are not passive recipients of personalized learning but rather active initiators of it.

It’s an important distinction. With remote learning likely to continue in some form at least through 2021, a greater degree of independence is being forced on students by structural necessity. Perhaps it’s time for schools to look anew at personalized learning, a model that in its best incarnations is not algorithm-led but student-led.

At Design39Campus, a public school in San Diego that opened in 2014 with a view toward personalized learning, there are no grade levels, and no one with the title of “teacher.” Instead, students are loosely grouped into “pods” roughly based on their age, and educators are known as “Learning Experience Designers,” or LEDs.

Last spring, as the school transitioned to remote learning, the biggest challenge for school cofounder and LED Megan Power was not managing her students but rather their parents. “We’ve trained the kids to be independent—to have an understanding of where they are and what they need to do,” she says. “And now the parents are taking a lot more of the lead.”

Still, she was pleased to see a group of her younger students step up and decide to create a game in order to master the concept of coin values during a spring unit on money. “It’s not the teacher telling them what to work on; it’s like a joint partnership,” she says.

Students are falling behind: School disruptions during the pandemic are taking a toll.

A student named Ishansh shared pictures of bread that he swabbed on a TV remote, a yoga mat, and other potentially germ-infested places, in effect creating a set of homemade petri dishes. Using a program he wrote in Python, he explained, he analyzed the germ growth on each slice of bread over time (and thoroughly grossed out his mom). “I feel a lot more confident and independent now,” he says, “because during the project I learned how to take the initiative and be more productive and organized.”

Self-awareness seems to come easily to Khan Lab students, who spend a week at the end of each term reflecting on their learning. “Metacognition develops with age, but we try to nurture it early on,” says Sonia Cho, head of Khan Lab’s Lower School.

Mott Haven Academy Charter School, founded in 2008 to serve children in the foster care system, stands in the shadow of the Major Deegan Expressway in the South Bronx. Though the academy has a very different student body than the Khan Lab School (500 students, the majority of whom are being monitored by child welfare services), its students have been relatively successful at learning during the pandemic—a reminder that any remote-learning strategy, particularly one that is personalized, requires that schools give educators the time and resources to invest in relationships with their students. At the academy, that happens through educator training, close coordination with social work staff, and family support services provided via nonprofit operating partner the New York Foundling.

As of early May, work completion and attendance was hovering around 95% for Mott Haven Academy’s middle school students, and around 85% for its elementary school students, despite ongoing challenges related to device and internet access. (The school gave cash grants to some families, so that they could afford to use their prepaid phones as Wi-Fi hot spots.) At schools serving similar communities, attendance rates have been far lower—if they are being tracked at all. As of June, according to the Center for Reinventing Public Education, fewer than half of districts nationally were requiring attendance or one-on-one check-ins.

Mott Haven Academy cofounder Jessica Nauiokas, who has been head of school for more than 12 years, says she’s “proud of the things we’ve been able to accomplish because of the priorities that we had before this crisis began.” Her staff knew which students were hungry, which were living in shelters, which had undocumented parents. The goal is for students to feel known, and also to remove barriers to their success. The coronavirus has been a reminder of just how daunting those barriers can be.

“We’ve already had two students whose parents have passed away from COVID,” she says. “Lots have lost grandparents, but these children are losing their primary caregivers. Just about the first person they reached out to tell was their teacher.”

User Center

User Center My Training Class

My Training Class Feedback

Feedback