Longitudinal analysis of blood cytokines in cohorts of hospitalized patients

Two-hundred twenty nine sequential plasma samples were collected frequently from 25 acutely hospitalized COVID-19 patients until death, or discharge from the hospital following recovery from disease. Samples were numbered from the day (D) of symptom onset and were all PCR-confirmed. All experimental analyses were performed in a blinded manner. The demographic and clinical information was unblinded for the authors by the hospital staff following data analysis and is presented in Source Data. After unblinding, the patients fell into three groups: (i) moderate patients released from hospital with no ICU admission (Non-ICU survived; NS series; n = 6); (ii) severe patients that were admitted to ICU but recovered from symptoms and were discharged from the hospital (ICU-Survived; IS series; n = 11); (iii) and COVID-19 patients in ICU who expired (Expired; E series; n = 8). Power analysis for sample size is presented in Suppl. Table 1 and Suppl. Equation 1. Distribution of COVID-19 patients and samples used in the study are shown in Suppl. Fig. 1. Most patients (80%) were symptomatic males between the ages of 44 and 75 years.

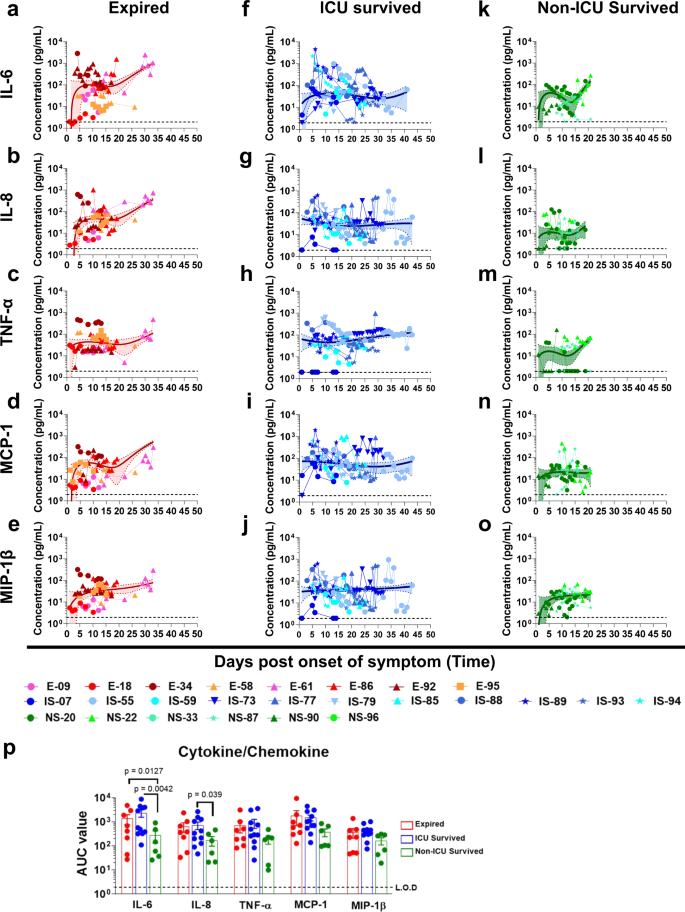

Cytokine (17-plex) profiling were conducted on all patients (Source Data). Prolonged elevation of multiple cytokines (IL-6, IL-8, TNFα, MCP-1, and MIP-1β) were observed in patients that were admitted to the ICU who either expired (red curves; Fig. 1a–e) or survived (blue curves; Fig.1f–j), compared with patients who were discharged from hospital without ICU admission (green curves; Fig. 1k–o). The area under the curve (AUC) were calculated for the first 20 days of hospitalization for these three cohorts to control for the duration of the samples collected so they were not impacted the window of samples collected. The differences in AUC between ICU vs. non-ICU patients reached statistical significance for IL-6 and IL-8 (Source Data and Fig. 1p). Serum samples from 15 normal healthy adults collected in 2010 were found to contain <10 pg/mL of either IL-6 or IL-8. Cytokine upregulation has previously been shown to be associated with severe cases of COVID-19 patients8.

Cytokine/chemokine levels in COVID-19 patients at different days post-onset of symptoms. (a–e); Expired patients (n = 8), (f–j); Survived patients (ICU; n = 11), (k–o); Survived patients (non-ICU; n = 6). IL-6 (a, f, and k), IL-8 (b, g, and l), TNFα (c, h, and m), MCP-1 (d, i, and n), and MIP-1β (e, j, and o) concentrations in 4-fold diluted plasma samples at various time-points after hospitalization of the COVID-19 patients were determined via a Bio-Plex Pro Human Cytokine Panel 17-Plex assay. a–o Expired patients (patient number’s starting with E); ICU-survived patients (patient number’s starting with IS); and non-ICU survived patients (patient number’s starting with NS). The trendline fits were performed for expired (red), ICU survivors (blue) and non-ICU survivors (green) using a non-linear regression model with polynomial distribution through the origin in Graphpad Prism. The trend line is depicted as solid colored line with the error bands representing 95% confidence interval shown as shaded colored area for each group. p Area under the curve (AUC) was determined for the five cytokine/chemokines from day 1 to day 20 of the three COVID-19 patient groups to control for the window of samples collected. Bar chart shows datapoints for each individual and presented as mean values ± SEM. The statistical significances between the groups of area under curve (AUC values) for “expired” patients (a–e; shades of red; n = 8 biologically independent individuals), “ICU-survived” patients (f–j; shades of blue; n = 11 biologically independent individuals), and “non-ICU survived” patients (k–o; shades of green; n = 6 biologically independent individuals) were determined by non-parametric (Kruskal–Wallis) statistical test using Dunn’s multiple comparisons analysis in GraphPad prism. The differences were considered statistically significant with a 95% confidence interval when the p-value was <0.05.

Development of neutralizing and hACE2-receptor blocking antibodies in hospitalized patients with different clinical outcomes

The majority of the hospitalized patients developed hACE2-blocking antibodies (black curves, Fig. 2), as well as neutralizing antibodies measured in a pseudovirion-neutralization assay (PsVNA50). In general, there was good agreement between the two assays (Suppl. Fig. 2), except for a few patients who retained high ACE2-blocking titers but showed low neutralizing titers at later days of hospitalization in two expired patients (E-58 and E-61) and two patients that survived after ICU admission (IS-55 and IS-77). Interestingly, not all hospitalized patients developed strong neutralizing titers. In each of the groups we identified individuals with either high or low titers, demonstrating discordance between neutralization titers and disease severity and outcome (Fig. 2a–d).

SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing antibody titers (PsVNA50) in plasma at various time-points as determined by pseudovirion neutralization titer 50 (PsVNA50) in Vero E6 cells are shown in colored curves, and the percentage of ACE2 inhibition values at different days post-onset of symptoms are shown in black curves. a “Expired” patients (n = 8); b “ICU-survived” patients (n = 11); and c “non-ICU survived” (n = 6) patients. Expired patients (patient number’s starting with e); ICU-survived patients (patient number’s starting with IS); and non-ICU survived patients (patient number’s starting with NS). Virus neutralization PsVNA50s titers were calculated with GraphPad prism version 8. Percent inhibition of hACE2 binding to RBD in presence of 1:100 dilution of COVID-19 plasma was measured by ELISA. The neutralization and ACE2-inhibition experiments were performed twice independently with similar results. d Area under the curve (AUC) was determined for the PsVNA50 or the percent ACE2 inhibition from day 1 through day 20 of the three COVID-19 patient groups to control for the window of samples collected. Bar chart shows datapoints for each individual and presented as mean values ± SEM. The statistical significances between the groups were determined by non-parametric (Kruskal–Wallis) statistical test using Dunn’s multiple comparisons analysis in GraphPad prism for the area under curve (AUC values) between “expired” patients (red; n = 8 biologically independent individuals), “ICU-survived” patients (blue; n = 11 biologically independent individuals), and “non-ICU survived” patients (green; n = 6 biologically independent individuals) did not identify any statistical significance (p > 0.05).

Epitope repertoire of antibodies in hospitalized COVID-19 patients using SARS-CoV-2 spike Genome Phage Display Library (SARS-CoV-2-S GFPDL)

To understand the development of IgM, IgG and IgA repertoires following SARS-CoV-2 infection during hospitalization, a highly diverse SARS-CoV-2-S GFPDL with >107.1 unique phage clones was used to evaluate plasma samples collected at early and late hospitalization time points from the same patients. The SARS-CoV-2 GFPDL displays epitopes of 18-500 amino acid residues with random distribution of size and sequences of inserts that spans across the SARS-CoV-2 spike gene. Recently, we demonstrated that the SARS-CoV-2-S GFPDL expresses both linear and conformational epitopes, including neutralization targets, that were recognized by post-vaccination sera15. GFPDL-based epitope mapping of monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) targeting SARS-CoV-2 spike or RBD identified the expected epitope recognized by these MAbs. Moreover, in the current study, the SARS-CoV-2 GFPDL adsorbed majority (>91%) of SARS-CoV-2 prefusion spike-specific antibodies in the post-infection polyclonal human plasma samples either from expired or survived patients, providing proof-of-concept for use of the SARS-CoV-2 GFPDL for epitope repertoire analyses of human plasma (Suppl. Fig. 3). Sera from uninfected individuals (collected in 2009) bound very few (<10) phages of the SARS-CoV-2 GFPDL.

The post-infection polyclonal IgM, IgA and IgG antibody-epitope repertoires were determined by GFPDL analysis conducted on polyclonal samples pooled from the first available time-point (within 1–4 days post-onset of symptoms) vs. plasma from the last time-point of either fatal COVID-19 patients (E-18, E-34, and E-58; Expired—<D4 & Expired—final sample) (shown in red in Fig. 3b, c, d), or non-ICU, surviving COVID-19 patients (NS-33 and NS-90; Survived—<D4 & Survived—Discharged) (shown in green in Fig. 3b, c, d). The total number of bound phages by IgM, IgG, and IgA antibodies from each patient group is shown in Fig. 3a. On the day of hospitalization, the numbers of IgM, IgG, and IgA bound phages ranged between 104–105 in both groups. The number of phages bound by the pooled samples from the latest time points increased by ~10-fold for IgG in both groups. However, the number of phages bound to IgM and IgA at the latest time point decreased in the survivors but increased in the fatal COVID-19 patients (Fig. 3a). The total serum antibodies in these patients were in the same range as has been observed for normal adults (IgG: mean 9.6 (range 7.1–12.9) mg/mL, IgA: mean 2.8 (range 1.7–3.4) mg/mL, and IgM: mean 1.9 (range 1.1–3.8) mg/mL).

Distribution of phage clones after affinity selection on plasma samples collected at early vs. late time points from hospitalized patients. a Number of IgM, IgG, and IgA bound phage clones selected using SARS-CoV-2 spike GFPDL on pooled polyclonal samples from “expired” patients (E-18, E-34, and E-58), collected from days 1–4 (Expired—<D4) following symptom onset and the last day before death (Expired— Final sample) or pooled polyclonal samples from “survived” non-ICU COVID-19 patients (NS-33 and NS-90) collected on days 1–4 (Survived—<D4) following symptom onset and the day of discharge (Survived—Discharged) from hospital. b–d IgM, IgG, and IgA antibody epitope repertoires of expired (red) vs. survived (green) COVID-19 patients and their alignment to the spike protein of SARS-CoV-2. Graphical distribution of representative clones with a frequency of ≥2, obtained after affinity selection, are shown. The horizontal position and the length of the bars indicate the alignment of peptide sequence displayed on the selected phage clone to its homologous sequence in the SARS-CoV-2 spike. The thickness of each bar represents the frequency of repetitively isolated phage. Scale value for IgM (black), IgG (red), and IgA (blue) is shown enclosed in a black box beneath the respective alignments. The GFPDL affinity selection data was performed in duplicate (two independent experiments by researcher in the lab, who was blinded to sample identity), and similar number of phage clones and epitope repertoire was observed in both phage display analysis.

The IgM-epitope repertoire was diverse and covered the entire spike protein including the receptor-binding domain (RBD) and the receptor-binding motif (RBM) in S1, and the fusion peptide in S2. No obvious difference were found in the epitope diversity of IgM antibodies between the two groups (Fig. 3b red vs. green). The IgG epitope recognition was also diverse, with immunodominant antibody epitopes at the N-terminal domain (NTD) and C-terminus of S1 domain, N-terminus of and β-rich connector domain (CD) and the HR2 domain at the C-terminus of S2, followed by HR1 domain of S2 in both the fatal cases and survived patients (Fig. 3c). Importantly, in the expired group, we observed minimal recognition of a short epitope sequences in RBD, and no binding to receptor binding motif (RBM) (Fig. 3c). The IgG antibodies in the non-ICU survived pooled plasma recognized the entire RBM region, and also bound to an immunodominant epitope in the fusion peptide of S2 domain. Interestingly, the IgA repertoire of the expired patients also had a “hole” in the RBD/RBM region (similar to the IgG repertoire of the same plasma pool, which was not seen with the pooled plasma from the surviving (non-ICU) patients (Fig. 3d).

Subsequently, we conducted IgM, IgG and IgA GFPDL analysis on pooled samples from ICU- admitted patients who survived (IS-07, IS-88, and IS-89) (Fig. S4). The IgG/IgA antibodies in these ICU-survivors did recognize the entire RBM region and fusion peptide in the S2 domain, similar to the non-ICU surviving patients (Suppl. Fig. 4 vs. Fig. 3c, d).

Overall, SARS-CoV-2 infection in these COVID-19 patients generated a diverse antibody repertoire across the spike protein. These included twelve antigenic regions and thirteen antigenic sites within these regions and were defined by at least 4% of phage clones obtained after affinity selection on IgM/IgG/IgA antibodies with at least one plasma sample at any time point (Fig. 4a, b). Most regions/sites (length of 34 to 239 amino acid residues) were similarly recognized by antibodies in all patient groups (shown in black in Fig. 4a, b). However, comparison of the IgG epitope repertoire between the expired vs. survived COVID-19 patients revealed that surviving patients contained IgG and IgA antibodies that bound to the large RBD site S6 encompassing the RBM (shown in green in Fig. 4a, b) and that was missed by the IgG as well as IgA antibodies from expired patients. In addition, the fusion peptide containing antigenic region S9 in the S2 domain (in green) was primarily recognized by IgG from surviving patients but not by IgG in fatal COVID-19 cases. Structural depiction of these antigenic sites on the SARS-CoV-2 spike (on PDB#6VSB) demonstrated that both antigenic site S6 (Fig. 4c) and site S9.3 (Fig. 4d) are surface-exposed on the trimeric spike23. These antigenic regions/sites in the S1 domain are not conserved among other coronaviruses. However, some sites in S2 show >50% sequence conservation across multiple human and bat CoV species (Source Data).

Antigenic regions/sites within the spike protein recognized by plasma antibodies following SARS-CoV-2 infection (based on data presented in Fig. 3). The amino acid designation is based on the spike protein sequence encoded by the SARS-CoV-2 Wuhan-Hu-1 strain (GenBank: MN908947.3) spike. The antigenic regions/sites discovered using the post-infection antibodies are depicted below the SARS-CoV-2 spike schematic. The epitopes of each protein are numbered in a sequential fashion indicated in black. Antigenic sites shown in green letters (SARS CoV-2 S6 and S9.3) were uniquely recognized by post-SARS-CoV-2 infection IgG (a) or IgA (b) antibodies only in the “survived” but not from expired COVID-19 patients (as shown in Fig. 3). c, d Structural representation of S6 (c) and S9.3 (d) antigenic sites depicted in green on the surface of a monomer in a trimeric spike (PDB#6VSB) with a single receptor-binding domain (RBD) in the up conformation, wherever available using UCSF Chimera software version 1.11.2. The RBD region is shaded in red (residues 319–541) on both structures. e, f Seroreactivity of COVID-19 plasma samples with the selected synthetic peptides covering epitope S6 (receptor-binding motif; RBM) and peptide S9.3 (fusion peptide; FP). Absorbance at 100-fold dilution of early first sample (E) or last (L) sample from SARS-CoV-2 infected individuals were tested for binding to RBM (panel e) and FP (panel f) in IgG ELISA. The statistical significances between “expired” patients (red; n = 8 biologically independent individuals), “ICU-survived” patients (blue; n = 11 biologically independent individuals), and “non-ICU survived” patient (green; n = 6 biologically independent individuals) groups were determined by non-parametric (Kruskal–Wallis) statistical test using Dunn’s multiple comparisons analysis in GraphPad prism. p-values <0.05 were considered significant with a 95% confidence interval.

To further evaluate the specificity of post-SARS-CoV-2 infection antibodies in serum to these two differential immunodominant antigenic sites in spike that were not bound at high frequency in IgG/IgA from COVID-19 expired patients using GFPDL analysis, these peptides were chemically synthesized and analyzed in ELISA (Fig. 4e, f). Using either the early or last plasma from survivors showed higher plasma IgG binding to the RBM peptide (Fig. 4e), that reached statistical significance in comparison between fatal vs. non-ICU survivors. On the other hand, binding to the fusion peptide (Fig. 4f) increased between early and late time points for the surviving patients (shown in blue and green), but not for expired patients, and reached statistical significance.

Therefore, the GFPDL analysis identified potential holes in the antibody repertoires of expired patients. Specifically, in the late stage of the disease, there was reduced RBM-and Fusion-peptide binding by IgG and IgA antibodies from expired patients compared with the patients who survived COVID-19.

Evolution of antibody binding and isotype class-switching against SARS-CoV-2 prefusion spike following SARS-CoV-2 infection in hospitalized COVID-19 patients

To determine the evolution of antibody response in these 25 COVID-19 patients during their hospital stay, quantitative and qualitative SPR analyses was performed for several dilutions (10-, 50-, and 250-fold) of polyclonal plasma from all time-points from each patient using recombinant purified SARS-CoV-2 prefusion spike protein. The conformational integrity of the prefusion spike used in our SPR assay was assessed using recombinant human ACE2 (hACE2), the SARS-CoV-2 receptor, that demonstrated a high-affinity interaction with an affinity constant of 6.7 nM (Suppl. Fig. 5). Representative sensorgrams of binding to the prefusion spike by serially diluted plasma (10-, 50- and 250-fold) from two patients are shown in Suppl. Fig. 6.

Control human plasma samples collected from healthy adults in 2008 showed <6 RU binding to the SARS-CoV-2 prefusion spike protein in SPR (Suppl. Figs. 6 and 7). We previously demonstrated that the optimized SPR does not show non-specific background reactivity against the SARS-CoV-2 spike proteins with plasma from unimmunized rabbits or rabbits immunized with an irrelevant antigen15.

In addition to measuring bound antibodies specific for the prefusion spike protein, the SPR assay was used to determine the relative contribution of each antibody isotype: IgM, IgG (including subclasses) and IgA in plasma antibody bound to prefusion spike in these COVID-19 patients (Fig. 5).

Serial dilutions of each plasma sample collected at different time points from the COVID-19 patients were analyzed for antibody binding to purified SARS-CoV-2 prefusion spike ectodomain (aa 16-1213) lacking the cytoplasmic and transmembrane domains (delta CT-TM), and containing His tag at C-terminus, was produced in FreeStyle293-F mammalian cells. Total antibody binding is represented as SPR maximum resonance units (RU) (black curves) of 10-fold diluted plasma samples from expired patients (a; patient number’s starting with E; n = 8), ICU-surviving patients (b; patient number’s starting with IS; n = 11) and non-ICU surviving patients (c; patient number’s starting with NS; n = 6). Isotype composition of plasma antibodies bound to SARS-CoV-2 spike prefusion protein for each individual COVID-19 patient at different time-points as measured in SPR. The resonance units for each antibody isotype was divided by the total resonance units for all the antibody isotypes combined to calculate the percentage of each antibody isotype (according to the color codes; IgM, black; IgA, blue; IgG1, red; IgG2 green; IgG3, orange; IgG4, fuchsia). All SPR experiments were performed twice blindly. The variation for each sample in duplicate SPR runs was <5%. d The area under the curve (AUC) of SARS-CoV-2 prefusion spike binding antibody levels (Max RU) for the COVID-19 patients who expired (red; n = 8 biologically independent individuals) vs. ICU-survived (blue; n = 11 biologically independent individuals) vs. non-ICU survived (green; n = 6 biologically independent individuals). Bar chart shows datapoints for each individual and presented as mean values ± SEM. e AUC of mean percentages of antibody isotypes IgM, IgG, IgA) bound to SARS-CoV-2 prefusion spike for the COVID-19 patients who expired (red; n = 8 biologically independent individuals) vs. ICU-survived (blue; n = 11 biologically independent individuals) vs. non-ICU survived (green; n = 6 biologically independent individuals). Bar chart shows datapoints for each individual and presented as mean values ± SEM. The statistical significances between the groups were determined by non-parametric (Kruskal–Wallis) statistical test using Dunn’s multiple comparisons analysis in GraphPad prism. The differences were considered statistically significant with a 95% confidence interval when the p-value was <0.05.

In the patients that were discharged with no ICU admission (NS series), the total antibody IgG binding increased from the day of hospitalization to the day of discharge. During that time, the IgM antibodies to prefusion spike were high on days 7–10 post-onset of symptoms and then class-switched with increasing contributions of primarily IgG1, followed by IgG2, with minimal IgG3 and IgG4. A small IgA component was measured in some of these patients that was <10% at most-time points during hospitalization (Fig. 5c).

The binding of antibodies to prefusion spike protein in half of the ICU patients who expired (Fig. 5a) or survived (Fig. 5b) showed binding curves, with initial increase in total antibody binding followed by a decrease in RU values (Suppl. Fig. 8a). The initial increase in spike-binding antibody titers were faster in the more severe cases (ICU admitted) compared with the non-ICU cases (Suppl. Fig. 8a). The overall prefusion spike binding antibodies were significantly higher in severe ICU cases compared with non-ICU patients (Fig. 5d).

The IgM responses trended higher in the non-ICU patients (Fig. 5e). In the case of IgG responses, most of the ICU patients (14 of the 19) contained >10% prefusion spike-binding IgG antibodies that comprised either IgG3 or IgG4 subclass, in addition to IgG1 response. Importantly, the isotype distribution demonstrated sustained high percentage of IgA binding antibodies in all ICU patients, either expired or survived (Fig. 5a, b), not seen in the non-ICU patients (Fig. 5c). The percentages of IgA antibodies bound to prefusion spike were significantly higher in ICU patients (either expired or survived) compared with the non-ICU patients (Fig. 5e).

Antibody affinity maturation during hospitalization comparing fatal vs. survived COVID-19 patients

In addition to total binding antibodies, it was important to determine if SARS-CoV-2 infection induced antibody affinity maturation against the viral spike protein. Technically, since antibodies are bivalent, the proper term for their binding to multivalent antigens like viruses is avidity, but here we use the term affinity throughout, since we measured primarily monovalent interactions15,20,22. Serial dilutions (10-, 50-, and 250-fold) of freshly prepared plasma were analyzed for antibody kinetics on SARS-CoV-2 prefusion spike captured via His-tag on the chip at low surface density to measure monovalent interactions independent of the antibody isotype. Antibody off-rate constants, which describe the stability of the antigen-antibody complex, i.e., the fraction of complexes that decays per second in the dissociation phase, were determined directly from the human polyclonal plasma sample interaction with recombinant purified SARS CoV-2 prefusion spike ectodomain using only sensorgrams with Max RU in the range of 10–100 RU. Off-rate constants were determined from two independent SPR runs.

In the expired COVID-19 patients, low antibody affinity (faster antibody dissociation kinetics) was observed to the prefusion spike with mean final day off-rate of 0.0173 per second (range of 0.045 to 0.0056 per second) during hospitalization (Fig. 6a and Suppl. Fig. 8b, red curve). In these fatal cases, minimal or no anti-spike antibody affinity maturation was observed from the initial sample to the last sample until their demise. Patients that survived after ICU admission demonstrated a gradual increase in antibody affinity over time with a mean final day off-rate of 0.0023 per second (range of 0.0071 to 0.0012 per second) (Fig. 6b and Suppl. Fig. 8b, blue curve). Importantly, the non-ICU patients demonstrated even higher antibody affinity maturation (2-log slower dissociation rates) with mean final day off-rates reaching 0.0012 per second (ranging between 0.0015 to 0.00096 per second) prior to their discharge (Fig. 6c and Suppl. Fig. 8b, green curve). The anti-spike antibody affinities (as measured by off-rates) were significantly higher in survivors (ICU or non-ICU) compared with the fatal COVID-19 patients (Fig. 6d). In agreement, significantly higher antibody affinity maturation (fold change in antibody off-rate of last time-point from first-time point during hospitalization) was observed in survivors (ICU or non-ICU) compared with fatal cases, with mean fold change in antibody dissociation rate of 61.1 for non-ICU survivor’s vs. 22.5 for ICU survivor’s vs. 1.97 for fatal cases (Fig. 6e).

a–c Polyclonal antibody affinity to SARS-CoV-2 prefusion spike protein for COVID-19 patients at different time-points post-onset of symptoms was determined by SPR. Binding affinity was determined for individual COVID-19 patients, a expired (in red shades; patient number’s starting with E; n = 8); b ICU-survived (in blue shades; patient number’s starting with IS; n = 11); c non-ICU survived (in green shades; patient number’s starting with NS; n = 6). Antibody off-rate constants that describe the fraction of antibody–antigen complexes decaying per second were determined directly from the plasma sample interaction with SARS-CoV-2 prefusion spike protein using SPR in the dissociation phase as described in Materials and Methods. All SPR experiments were performed twice blindly. The variation for each sample in duplicate SPR runs was <5%. The data shown is average value of two experimental runs. Off-rate was calculated and shown only for the samples that demonstrated a measurable (>5 RU) antibody binding in SPR. d The average antibody affinity against SARS-CoV-2 prefusion spike is shown for the final day samples from the COVID-19 patients who expired (red; n = 8 biologically independent individuals) vs. ICU-survived (blue; n = 11 biologically independent individuals) vs. non-ICU survived (green; n = 6 biologically independent individuals). Bar chart shows datapoints for each individual and presented as mean values ± SEM. e Fold-change in antibody affinity against SARS-CoV-2 prefusion spike was calculated for the final day samples compared with the first day sample from each of the COVID-19 patients who expired (red; n = 8 biologically independent individuals) vs. ICU-survived (blue; n = 11 biologically independent individuals) vs. non-ICU survived (green; n = 6 biologically independent individuals). Bar chart shows datapoints for each individual and presented as mean values ± SEM. The statistical significances between the groups were determined by non-parametric (Kruskal–Wallis) statistical test using Dunn’s multiple comparisons analysis in GraphPad prism. The differences were considered statistically significant with a 95% confidence interval when the p-value was <0.05.

User Center

User Center My Training Class

My Training Class Feedback

Feedback

Comments

Something to say?

Log in or Sign up for free