An unusual new ‘homologous series’ of barium compounds forms a potentially infinite sequence of related structures with predictable unit cells. The US team behind this discovery says that understanding such structure–composition relationships could improve the ability of machine learning models to discover new inorganic materials.

Homologous series are commonly seen in organic chemistry, where sequences of compounds with repeating units can be described by a general formula – famous examples include straight chain alkanes and alkenes. Similar sequences can exist in solid-state inorganic materials, although they are less widespread. Examples include non-stoichiometric titanium oxides and the 2D halide perovskites used in solar cells.

In the new work, inorganic chemist Mercouri Kanatzidis of Northwestern University in Illinois and his colleagues found that a series of barium compounds form closely related solid structures that vary in a predictable way when a single parameter is changed. ‘That means if you have one member and you know you’re in a sequence, you know what the next member is going to be,’ says Kanatzidis.

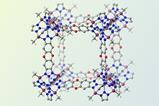

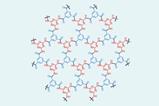

The researchers started with barium antimony telluride (BaSbTe3). They then substituted increasing proportions of the tellurium with its fellow group 16 element sulfur. The sulfur and tellurium atoms would intuitively have been expected to disperse randomly around the anionic sites, forming a solid solution. However, the researchers showed theoretically that the sulfur, being more electronegative, preferentially incorporates at more electron-rich sites in the crystal lattice. This causes second-order effects on the structure, with the telluride anions becoming increasingly electron-poor as the proportion of sulfur increases. ‘A solid solution doesn’t happen,’ says Kanatzidis. ‘Instead the material responds by finding another way to order the tellurium and sulfur, forming another member of the homology. That’s the part that’s just out of this world.’

Establishing chemical principles

The researchers synthesised ten members of the homologous series, with ever-increasing structural complexity. The final member, BaSbSTe2, contains an instability in its electronic structure called a charge density wave. At high temperatures or low pressures, such charge density wave materials often show superconductivity. The researchers now intend to use the results to try to predict new types of superconductors rationally – something not presently possible.

Kanatzidis and his team also point out that while machine learning is increasingly being used to design new chemical structures, these techniques are best at predicting materials within established structure types. As a result, these tools have been more successful in areas like organic chemistry, where more ‘extensive sets of chemical principles have been established’, whereas they have struggled to find truly novel solid-state materials. Kanatzidis says that findings like the new phase homology will provide useful training data for machine learning, enhancing its predictive power.

Materials chemist Leslie Schoop from Princeton University in New Jersey describes the work as ‘very solid’, and adds that researchers will need to examine the new materials for ‘any relevant properties that are worth pursuing in detail’. Schoop, who has previously expressed concern about autonomous materials discovery methods, also believes that relationships like those uncovered by Kanatzidis’ team could help to improve AI’s ability to tackle challenges in inorganic chemistry. ‘We need to start implementing this kind of thinking that actually leads to new material discoveries into AI algorithms,’ she says.

References

H Zhao et al, Science, 2025, DOI: 10.1126/science.aea8088

User Center

User Center My Training Class

My Training Class Feedback

Feedback

Comments

Something to say?

Login or Sign up for free